Dustin Hoffman's Quartet has debuted a new clip exclusively on Digital Spy.

The footage has Billy Connolly's former opera singer Wilfred Bond hitting on Sheridan Smith's character without success.

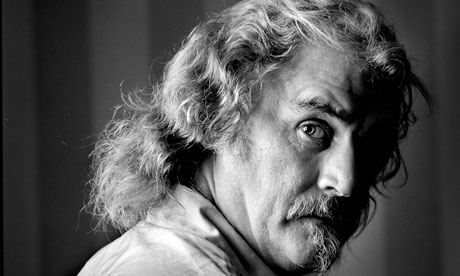

Billy Connolly: My family values

The actor and comedian talks about coming to terms with his children growing up and the joy of being a grandparent

Elaine Lipworth, The Guardian, Saturday 22 December 2012

Billy Connolly: 'All my kids are quite funny.' Photograph: Dominic Lipinski/PA Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

I am a kind of Victorian father. I haven't caught up with the mood of the age yet, although I look and speak as though I have. I still care about all my children [he has four girls and a boy], and worry about my girls and always make sure they are on the right lines. When we're crossing the road, I go, "Righto, here we go!" as if they're six years of age. Amy, who is 24, has her own apartment. But the other night she was going out from our house and she said, "See you later," and I said, "Oh, when will you be back?" She said: "I'm going to my apartment." I said: "Yes, but when'll you be back?" She said: "I won't be back, I've got an apartment." I went: "Oh, yeah."

Pamela [Stephenson] is a much better parent than me because she knows what's right and wrong, being a psychologist. She knows a great deal more about behaviour than I do. I panic and get worried about the girls and think: "Ahhh, something is wrong, she's out too late!" Pamela just says: "Oh, at this stage she should be doing that." But I think I'm also a product of my generation. As a family, we are all very loving. We still kiss each other. Jamie's 42 and he still kisses me good night. We've just got back from fishing in Mexico. We were staying in two rooms, in a fishing lodge and at night we would have a cigar and at the end of the evening, we'd say: "OK, you going to bed? Good night, give us a kiss."

It's very difficult bringing up the girls without spoiling them because you sound like an old bore when you start saying: "Oh, I had to finish every brussels sprout on the plate when I was a boy." It's true though, I used to go to the movies and put my sprouts in my pocket and pretend I had eaten them. I've stayed away from that kind of behaviour towards them, but obviously we have lived well on my earnings and I try my best to show them the value of things. But you can't be too strict with them, because you just sound like a whinge-bag. Anyway, spoiling them is buying them things in place of love, and they've never been in that position.

I'm a great family guy, I'm all for keeping them all together and it's getting sad now because the girls have got boyfriends and they don't want to come home for Christmas. All that kind of stuff is sad, but you just have to get used to it and grow up a wee bit.

My children and I are pals and allies, they're lovely. We all get on great. But I never carry photographs of my wife and kids because they make me sad. I'm not one of those guys who gets to the hotel room and puts the framed pictures up. I really can't do it. Photos make you miss them more.

Always tell the kids the truth. When they ask where they come from, don't give them that gooseberry bush nonsense, just tell them – they'll appreciate it much more. If they say, "Did you take drugs?", if you did, say yes because they'll find you out. And if you say, "I tried marijuana and I hated it, it was horrible," and then they try it and it isn't horrible, they'll think you were lying about marijuana and wonder whether you were lying about heroin and could try that as well. I am totally open with my children.

All my kids are quite funny. They all really enjoy making me laugh. Scarlett works in an art gallery in Soho here in New York, Cara is making documentary films and Amy is studying to be an undertaker. She was working as a dress designer in Los Angeles and she got fed up with it. She saw an advert for an intern in a cemetery and she loved it the second she did it. It's the truth! She loves it.

Pamela saved me without being ruthless with me when I was drinking and smoking, by saying: "Look, if you don't give up the way you're living, you're gonna die. And I don't want to be there watching it when it happens." I haven't had a drink for 28 years. With Pam, I discovered that you could not get away with anything. When I married her I had to own up to everything, which no one had ever asked me to do before. I learned to be honest with myself, which was great.

The character I play in Brave – the dad – does a lot of shouting and thumping around and the mother does the heavy work. And I've found that in my own life, I do a lot of "this must be done and that must be done" but most of "it" is done by Pamela. My marriage to her has lasted because she knows how to do things. She knows much more than I do about technical stuff and how to do practical things, who to phone when you need to get something done in the house. I know bugger all. I swim along dreaming through life and she allows me to do that. She has taken on the male role and I have taken on what people used to think was the female role.

It's brilliant being a grandfather. My grandchildren – Walter is 12 and Barbara is 10 – are the best. When you have children in the first place and you can see the genetics, you see who they look like and it changes all the time. One day your son looks like your wife, one day he looks like you. It's the same with grandchildren. Cara burst out laughing the other day. I said, "What's wrong?" She said, "Look at your feet." I was standing next to Walter and I looked down and realised that our feet are identical. You'd think they'd just been moulded in a shop. With grandchildren you understand that the generations go on and on and on.

Source (including photo): Guardian

Lucy Kellaway talks to Billy Connolly

He has had Britain howling with laughter for decades. Now 70 and showing no signs of slowing down, the comedian opens up about getting old, forgiving his father – and the beauty of swear words

Billy Connolly is standing with his back to the door, singing raucously to himself. From behind, he looks slightly frightening – a mane of wild white hair, a black T-shirt, black jeans and a big tattoo on his left biceps – but then he turns and eyes me benignly through round tortoiseshell glasses. I’m not sure who he reminds me of most: King Lear, David Hockney or Ozzy Osbourne.

He invites me to sit, while he paces restlessly, checking the thermostat of the Soho hotel room.

Tell me about your hair, I say.

It is not the most obvious place to start with Scotland’s most famous comic, film star, abused child, artist, former alcoholic and all-round icon, but I’ve been taking lessons in how to interview him from a world authority – Connolly’s wife, Pamela Stephenson.

I started by watching a clip of the couple’s first meeting on the set of Not the Nine O’Clock News in 1979. Stephenson is wearing false teeth and pretending to be Janet Street-Porter. She talks broad cockney; he talks broad Glaswegian. The gag is that they can’t understand each other.

I then watch a clip from just two years ago; this time Stephenson doesn’t have false teeth, though she has false everything else: boobs, face etc. No longer a comedian, she is a sex therapist and has installed her husband on the couch to analyse him for her viewers’ entertainment.

She starts like this: “It seems to me that hirsuteness is quite important to you. Help me to understand why.”

This elicits a long answer about his need to hide, about being himself, about being attractive, about the classlessness of hippies. But when I ask him the same thing, he says: “It comes from an inability to decide what to do with it between films, so I leave it alone.”

I point out that he didn’t say that to his wife.

“Didn’t I?” he says. “Ach, it depends what day of the week it is.”

The previous night Connolly was at the London premier of Quartet, a light comedy directed by Dustin Hoffman set in a home for retired opera singers. He plays Wilf, an amiably lecherous old geezer with short hair and clad in a tweed jacket. I say the look suits him.

As retired singer Wilf in 'Quartet'

“Ach,” he says. “A lot of women said that last night, that I looked handsome. But I felt like a big Tory.”

The film is all about the indignities of ageing. But Connolly, who turned 70 in November, tells me that he’s spent his life looking forward to growing old (which sets him apart from Stephenson, who has paid frequent visits to the cosmetic surgeon “because I want to be a babe”).

“I always wanted to be old as a wee boy,” he says, swinging his cowboy-booted feet on to the coffee table. “We used to go to a swing park and there were always loads of old men in the shed playing dominoes. They always had knives – that’s what I liked about them. I like old men very much.”

I protest that old men are surely no nicer than anyone else.

“Aye,” he says, changing tack. “I think young arseholes tend to become old arseholes.”

One of the difficulties with interviewing Billy Connolly is that he says one thing one moment and another the next, his thoughts following a curious pattern of their own.

So his mention of knives leads him to cigarette cards and from there to self-defence and the body language of giving directions.

This ability to free-associate is part of his comic genius. Since he started amusing his fellow welders in Clyde shipyards nearly 50 years ago – he has never planned his performances, or written down a single word. Instead, he meanders all over the place, laughing at his own jokes as he does so, giving marathon performances that last up to four hours.

I wonder if he fears for his ability to go on doing it as he gets older. In the film, his co-star Maggie Smith (“Oh God I love her, she makes me scream with laughter”) plays a retired diva who is so upset at no longer being able to reach the high notes she has renounced singing altogether. Connolly says that when it comes to making people laugh, age doesn’t matter.

“It’s nothing to do with ageing,” he says. “I remember in my twenties, saying: f*** I hope it turns up tonight. If you look at Doddy – Ken Dodd – he’s busier than most people I’ve ever known. Some people accept that styles have changed and move along. Others say, f*** it I’m out there, this is my trade and I’m going to practise it.”

But then he tells me that despite recent accolades – he’s been voted the most influential British comedian of all time and has just been given a Bafta lifetime achievement award – he finds the idea of performing more alarming as he gets older. “Maybe I see the pitfalls and threats more than I used to.” But when I ask what they are, he says there aren’t any.

“I get great adoration, sometimes guys shake when they’re talking to me. A man cried last night. I just put my hand on him and stroked him a bit. He’d seen me in newspapers and films and on the stage and all that and there he is talking to me and I’m talking back to him and he got overwhelmed and his lip started to go. It’s weird, it’s lovely.”

. . .

Not everyone, however, was so awed. Later on he says: “Last night a guy got a bit iffy with me, you know, smart-arse about my performance. He said I was less than good. You know how the British do that British put-down thing that they think is funny?”

The Scottish comedian was not amused.

“I just turned and walked away in the middle of his sentence.”

This, it seems, is a trick he is getting into the habit of. Twice during his last tour of Britain he stormed off stage in response to heckling from the audience. When I mention this, Connolly waves his hands dismissively.

“Generally it’s made into something it isn’t, it’s no big deal. I wish journalists would just f***ing ask what it is and I would tell them. Once I’ve done my two hours it’s my time. After [that] I don’t want to be shouted at because I’m in a funny mental place.”

What is shocking – and almost sweet – about this is not that Connolly is so sensitive to both his detractors and his fans – it’s that he’s so unashamedly open about it. Suddenly I think of Wilf, who also lacks any sense of propriety – though in his case it’s as a result of a stroke. Connolly, it seems, never had one to lose, or if he did he quickly figured out that a great living could be made by dispensing with it.

“I speak the way I think. I give it a voice. And other people will think one way and speak another.”

And what he thinks about, often, is the body.

“I blame myself for that,” he says. “About bums and willies and going to the bathroom and venereal disease and all those things. That was the level I came in ... I broke a lot of ground there.”

©Alan Davidson/Picture Library

With his future wife Pamela Stephenson in 1982

Since he went on Parkinson in 1975 and told the joke about the man who killed his wife and buried her with her bum sticking out of the ground so that he had somewhere to park his bike – Britain has been howling with mirth at Connolly’s body parts.

While he’s been delighting audiences with tales of his prostate exam, Stephenson has been making a living telling tales of his emotions – and has written two bestselling books chronicling them.

Doesn’t he mind, I ask, when she starts describing to everyone just how he felt when his first wife – a recluse and an alcoholic – died? He shakes his head. “Who better to tell it? Some f***ing journalist?”

Stephenson’s interpretation of Connolly is not always flattering: I read something recently in which she said he was slightly autistic as well as suffering from an attention deficit disorder.

“Did she?” He laughs fondly. “She’ll accuse me of anything. I don’t think I’m autistic, but I do have attention deficit disorder.”

And then his mind is off on another excursion: he tells me that Stephenson has just emailed him a list of all the different words for depression, as he is planning to write a song in which the word “blues” is replaced by synonyms. He laughs for a long time, delighted by the idea. When he has stopped I ask if he suffers from the blues himself.

“Sometimes I plunge into it, headlong, but the clown with a tear is a myth – that comedians are really dark and tortured and troubled.”

It’s odd that he says this, as he seems to fit the mould of damaged comedian so perfectly. His mother walked out when he was four, he was brought up by two wicked aunts, who used to hit him and rub his nose in his soiled underpants, and he was later abused by his father.

“Well I come from a dark place but it doesn’t make me dark”, he says. “My ambition was always to be as funny as ordinary people are; as the regular working guys are.”

Yet for all of his admiration for the common man, Connolly has left them long behind. He is a friend of Prince Edward and countless celebrities, and owns three huge properties as well as a yacht. People are always complaining that his swanking around is a betrayal of his working-class roots.

“They’re just wankers,” he says. “That’s the press talking; they’re talking shite as they usually do. I have deep, deep distrust of them. I see them as my enemy. I’ve had years of experience of the vile f***ing vitriol.”

It strikes me as strange that Connolly is so full of rage at journalists (who as far as I can see have been more nice than nasty over the years), but when you get him on to the subject of people who he has real reason to hate – his father and mother for a start – he is all mildness.

“Well I loved my father. I didn’t know my mother very well. I didn’t meet her from when I was four until I was in my twenties,” he says evenly, as if it was of no matter.

The reason he forgives them is partly thanks to a “wee book”.

“I think maybe Pam gave it to me. It said there’s no such thing as hate, there’s only love and fear. I forgave my father for all that had gone on and it took a huge load off me. It was like having a rucksack taken off your back.”

This sounds like psychobabble to me. History shows that there is such a thing as hate.

“Well it manifests itself as hate but I think it’s based on fear and sometimes it’s encouraged by the f***ing Daily Mail.”

. . .

Thus far in the interview he has said the f-word 27 times, but instead of finding it repetitive or limiting, I like it. On his lips the word is both funny and melodic.

“It’s also rather beautiful,” he says. “In sport, you say he whacked it into the top right, it was f***ing beautiful. There’s no English word to replace that.”

So why do people go on being shocked by the f-word?

“Because they’re middle-class wankers.”

And then he says: “In America they seem to have just discovered Kant.”

This strikes me as a strange turn for the conversation to have taken. But then I realise he didn’t say that: we are still on obscenities.

“I went to see a movie the other night, Seven Psychopaths, which you must see, it’s f***ing great, and they use it brilliantly, you c***. They’ve got it right at last.”

He then starts on an inspired rant about

how the c-word never appears on its own. “Usually it’s a something c***. Like, she’s a nasty c*** that one.”

My time is nearly up, but before it is I want to ask him about his newest accomplishment – drawing. Earlier this year there was an exhibition of his work, including a rather nice picture of a mummified woman in a belted dress with two heads.

I ask what I’d have to pay to own it.

“I’m not talking about that. I don’t talk about money. It’s vulgar.”

But isn’t that rather middle class?

“Money’s a boundary because it makes people feel inadequate when they shouldn’t.”

Yet for all that Connolly isn’t scared of flaunting it. As well as the yacht and the houses in New York and in Malta, he owns a castle in Scotland called Candacraig. This is now available for hire to corporate groups, who for nearly £4,000 a night can enjoy an orgy of tartan and try to imagine the presence of the many Hollywood celebrities that the website promises are regular visitors.

I can just about see the attraction from the guests’ point of view. But I struggle to see why the owner would want corporate fat cats sleeping in his bed and going through his bathroom cupboard.

“I don’t care about that,” he says. “I’ve told everybody all my secrets.”

‘Quartet’ is released in cinemas on January 4

Source (including photos): Financial Times

No comments:

Post a Comment